Where to Start with Sidney Lumet

American director Sidney Lumet grew up immersed in the world of theater. His parents, Polish-Jewish migrants to the United States, were veteran actors of Yiddish theater and, as a child, Lumet himself performed in Yiddish theater, as well as on the radio, before making his Broadway debut aged 11. He studied acting at the Professional Children’s School of New York and Columbia University and, following a 4 year stint in the U.S Army during WWII, was part of the inaugural class at New York’s Actors Studio.

Lumet began directing off-Broadway theater in his early 20s and, by 1950, he had moved into television. His first feature film,12 Angry Men, was released in 1957 to critical acclaim and, despite being a disappointment at the domestic box office, established him as a director particularly skilled in the art of adaptation. A good chunk of his films originated on the stage or were adapted from novels.

Lumet focused much of his attention on gritty crime thrillers and political dramas, exploring themes of corruption, social injustice, and the disillusion of the American Dream. Many of his protagonists were anti-heroes, rebelling against the law and systematic oppression, driven not by morality but by passion and heart. He seemed most at home among the savage beauty of New York City and in intimate, character-driven stories.

Lumet’s background in acting made him “an actor’s director”, and his experience in television taught him efficiency, saving money and delivering his films on time. Over the span of four decades (between 1957 and 1997), Lumet directed 39 movies. On average, that’s one movie per year. Between his debut and 2007’s swansong Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Lumet was nominated for five Academy Awards. And, though he never won, he did receive an Honorary Academy Award in 2005 for his life’s work and dedication to the craft of filmmaking.

With such a long and storied career, it is certainly difficult to know where to begin. Here at The Film Magazine, we have created this guide to help navigate through Lumet’s dense filmography, highlighting three entry points that best showcase his style and artistry. This is Where to Start with Sidney Lumet.

1. 12 Angry Men (1957)

The beginning, it turns out, is a very good place to start.

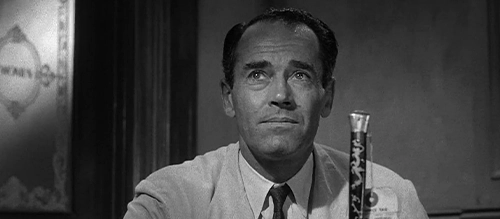

Sidney Lumet’s 1957 feature debut, 12 Angry Men, is based on the 1954 teleplay of the same name by Reginald Rose, initially staged as a CBS live production and later rewritten as a stage play in 1955. The film stars Henry Fonda as one of 12 jurors who are tasked with deciding whether a young man on trial for allegedly murdering his father is found innocent or guilty. When Fonda’s character is the only one to declare the boy innocent, the men are forced to re-examine the evidence and confront their own prejudices.

12 Angry Men is the kind of story that Lumet explored numerous times over the course of his career. While the director’s 1973 adaptation Serpico explores the corruption within law enforcement, 12 Angry Men instead deals with the institution of Law and Order itself, eventually exposing it for the imperfect system that it is. Lumet was always at his best when examining the pillars of our society that we are told to put our faith in, often bringing to light how these pillars fall short of delivering true justice, especially to those in marginalized communities.

The film takes place almost exclusively inside a small deliberation room during a blistering summer’s evening. Lumet’s skill in blocking his actors, something he was able to master during his time in theater and television, is vital to the film’s success. In less capable hands, it’s easy to imagine how scenes with a dozen people might feel messy and confused, but with Lumet, every frame is intricately arranged, every movement so precisely choreographed. 12 Angry Men is fluid and natural, but visually interesting enough to keep us engaged without ever changing locations. In addition, the film contains some of the best acting ever seen on screen – there isn’t a single weak link in the cast.

As with all of Lumet’s films that deal with themes of societal rot and the mistrust of authority, as well as racism and prejudice, 12 Angry Men feels downright modern and is as relevant today as it was decades ago. It was nominated for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay at the 30th Academy Awards and is often ranked among the ten best courtrooms dramas ever made.

2. Murder on the Orient Express (1974)

Murder on the Orient Express is a pallet cleanser of sorts for those unfamiliar with Sidney Lumet’s more hard-hitting work, and it highlights the artist’s range as a filmmaker. In this 1974 whodunit, adapted from Agatha Christie’s popular mystery novel of the same name, Lumet trades in urban decay for lush European countryside. A stylish period piece, Murder on the Orient Express feels like a call back to early classics of the 30s and 40s, especially given the casting of Golden Era icons Ingrid Bergman and Lauren Bacall.

The movie stars Albert Finney as Hercule Poirot, Christie’s most famous Belgian Detective, who, in 1935, boards a train bound for London at the last minute thanks to his old friend and director of the company, Signor Bianchi (Marti Balsam). What starts out as a seemingly uneventful train ride devolves into chaos when one of the passengers is found dead in his compartment. Poirot must piece together the events of that evening and, through his interrogation of each passenger on board, uncover a plot far more complicated than he could even imagine.

With Murder on the Orient Express, we once again find ourselves in close quarters, but unlike with 12 Angry Men, Lumet uses the cramped compartments and train cars to create a deliberate sense of claustrophobia. Each frame is organized chaos. People bump into each other, constantly battling against the walls and furniture of the train’s confined space. It’s a deeply entertaining ride and its runtime goes by in a flash.

There’s a whimsical quality to the film, with its lavish costume pieces and soft edges of light glimpsed through the train car windows. But being that it is a Sidney Lumet film, there is a rotten core found underneath it all.

It’s an obvious inspiration for Rian Johnson’s recent, wildly successful mystery, Knives Out. And, as with that movie, turns the very idea of justice on its head. Here, finding and arresting the murderer isn’t as important as discovering why the crime was committed in the first place. Through the performances he captures, Lumet reveals the lengths people are willing to go to when the justice system fails them. In the end, you may find yourself hoping for a different outcome than you were expecting.

3. Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Based on a real-life bank robbery that took place only three years before the film was made, Dog Day Afternoon tells the story of Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino), who intends to rob a bank in Brooklyn along with his partner Sal Naturile (John Cazale), in order to get the cash for his wife’s (Chris Sarandon) sex change operation. But, when Sonny discovers that the bank deposit was recently picked up and the vault is empty, he and Sal find themselves in a hostage situation that leads to deadly consequences.

Dog Day Afternoon is a pretty radical film, even by today’s standards. It’s a film about anarchy and it is unapologetically queer. The cops, along with the FBI, are regularly portrayed as incompetent and trigger happy, while the media sensationalizes the entire situation, giving voice to rampant bigotry and homophobia that still persists today. Through humanizing a character like Sonny, while never sugar coating his personal failings and flaws, Lumet asks us to empathize with a man who turns into a criminal not because he’s a bad person but because he feels as though he has nowhere else to turn.

The film is split into two parts and there is a deliberate tonal shift at the halfway mark. The first part of the film is kinetic, everyone always in motion. It’s deeply funny at times and leans into the absurdity of the situation. It’s a slow burn and Lumet passes the point of no return before we realize it. The last half of the film grows darker with every minute as we race head first towards a drastic conclusion.

One of Lumet’s talents as a director is his understanding of acting, his ability to get the most out of his cast and guide them in the right direction. Dog Day Afternoon is arguably one of star Al Pacino’s best ever roles, and that’s partly because Lumet recognizes what Pacino does best and uses that to his advantage.

While there are some obviously outdated elements in the film that come across as transphobic in retrospect, it’s worth noting how much care Lumet put into trying to avoid clichés, making sure his queer characters were portrayed with dignity and humanity. Having a huge star like Al Pacino play a man who is at odds with the stereotypical macho man of the time period was huge and is rightly recognized as a milestone in the history of queer cinema.

Recommended for you: Where to Start with Orson Welles

Sidney Lumet knew how to tell stories about those who exist on the outskirts of society. Those who are othered, who feel like they don’t belong. His characters were often flawed and rebellious and weren’t afraid to question authority. His unmatched work ethic, along with the support he offered his actors, made him a singular artist with a distinguishable style and flair, and his loss is one that continues to be felt. But, as Lumet himself said, “Good style, to me, is unseen style. It is style that is felt.”